American Art Collector magazine has featured my work in the past, and it is always an honour to be invited to do so again. Below you can read a recent interview about my latest body of work for my 6th solo exhibition at the George Billis Gallery in Los Angeles.

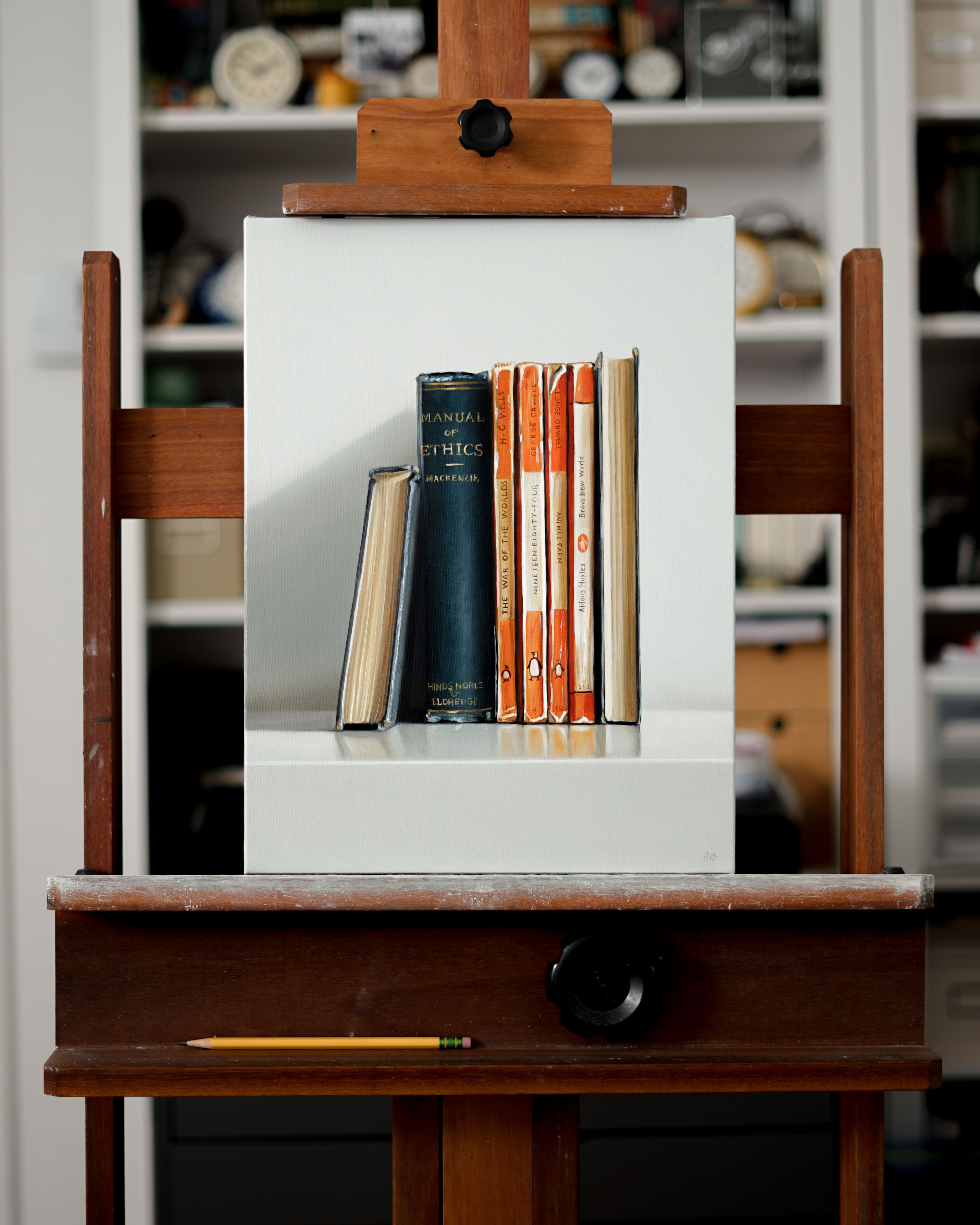

British Columbia artist Christopher Stott introduces a new collection of work displayed at George Billis Gallery in Los Angeles, California, through March 26. He continues to paint in his distinctive, realistic style, featuring still life, vintage objects like typewriters, box cameras, clocks and books. In keeping with the tradition of the early Dutch Masters, who have had a huge influence on his work, his pieces are full of significance and hidden meaning.

“At first glance, Stott’s paintings are elegantly refined compositions of objects on a monochromatic background,” says Tressa Williams, director at George Billis Gallery, “but digging a little deeper, the viewer falls down a rabbit hole of symbolism…Stott is part of a new generation of representational painters pushing the genre forward in fantastic ways.

It’s true that Stott has been painting the same genre, always still life objects. “In fact,” he says, “the telephone is the first object I ever painted 20 years ago.” He notes that a vintage, black rotary phone was the first object given to him in art class to paint. “What makes it still fresh?” he continues, “the idea is still relevant to today. With a receiver, you’re both talking and listening. You must stop and listen before talking; it’s a one-on-one conversation. Now, we live in a world where everyone screams over everyone else, but no one is listening.”

In Telephone Receiver I, a highly realistic black telephone on a gray background with a pencil nearby, one can clearly see the simplicity behind his vision. “The idea behind this is very subtle,” says Stott. “I’m not telling people to shut up and listen but rather, offering a meditation on real and meaningful conversations.”

The formal aspects of painting are also important to Stott, which goes hand in hand with history. “I really think that good art is connected to art history,” he says. “It has to have a bridge or passage directly to the history of painting. My subjects are old enough to be in our living memory, but the style, technique and composition are hundreds of years old.”

This is illustrated in The Interpretation of Dreams 112021, featuring a collection of vintage books with a clock on a white shelf. The way Stott uses these props is reminiscent of master still life painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. “He was the first to have stepped out of academic painting and painted strangely intimate, quiet paintings,” says Stott. “[The new collection] is a direct homage to paintings done in 1766. The same ideas of what they were doing several hundred years ago are still relevant to us now.”

Stott utilizes the same techniques that Dutch masters were using 400 years ago. He works in many layers to create a luminous effect under different lighting. It’s also very much about balance and symmetry for Stott, which is represented in his clock pieces. For instance, 10:10, No. 10. is painted on a 10-by-10-inch canvas with the clock hands set to 10:10.

A component also near to the artist’s heart is the history of vintage objects and even the process of searching them out. “For this particular show, I want the experience to be how I experience walking into an antique shop or museum,” Stott says. “You come upon them and look at them a little closer.” The show will have smaller paintings with several hanging closer together in groupings, so as to mimic this feeling. He adds, “I [want people to see] how I like to isolate these items and give them a new life.”